One Paragraph Summaries of Top Papers for Understanding Bank Money Creation and Its Economic Effects

I consider these papers to be some of the most important and seminal papers for understanding bank money creation and its effects on economic, social, environmental, and political stability and welfare.

Papers are organized by topic:

Why the US Congress outsourced money creation to for-profit private banks

Contraction in bank money creation causes financial and economic crises

Bank money creation can be used to end financial recessions overnight

Financial recessions are particularly damaging to democracies

Why the field of economics has mistakenly left bank money creation out of its models and teaching

Banks Create the Money They Lend

100% of the money that banks lend is freshly created money. It does not come from depositors’ money or central bank reserves.

Money Creation in the Modern Economy (McLeay 2014)

Published by the Bank of England in 2014, this explains how 95% of the money in the economy is created by commercial banks when making loans. Every single time they make a loan, they create 100% of the money that they lend out by simply typing it into their accounting records. The only thing that directly constrains banks’ ability to create new money in this way is the availability of willing and credit-worthy borrowers. The paper points out that these truths contradict what is taught in most mainstream economics textbooks today. Despite what is taught in schools, banks do not lend out deposits that savers place with them, nor do they ‘multiply up’ scarce central bank reserve into new loans through a process called ‘fractional reserve lending’. Read my summary of the paper here.

Dozens of central banks, banks, and banking scholars have published similar statements. The New Banking Consensus Database contains more than 150 cited quotations.

Analysis of bank accounting software confirms that banks create 100% of the money they lend

A Lost Century in Economics (Werner 2014)

This paper, published in the International Review of Financial Analysis by Oxford-trained banking professor Richard Werner, has two main thrusts: (1) It shows that bank accounting software is programmed to create new money every time a bank makes a loan and (2) it examines a century of economics literature in order to illuminate how and when the economics profession became erroneously convinced that banks lend out depositors’ savings and/or multiply-up central bank reserves.

Legal scholars confirm the statutory privilege that enables banks to legally create 100% of the money they lend

The Finance Franchise (Omarova 2017)

Cornell University legal scholars with decades of experience in banking regulation published this paper to illuminate the reality that banks are the creators of the nation’s money supply and that most banking regulations are poorly fitted to that reality. They argue that the understanding that banks accumulate and lend out a scarce supply of money is mistaken. Instead, they suggest it is more accurate to think of banks as franchisees to whom the government (the franchisor) has outsourced the right to expand and contract the the nation’s money supply through money creation when making loans.

Why the US Government Outsourced Money Creation to Private For-profit Banks

Why Supervise Banks? The Foundations of the American Monetary Settlement (Menand 2019) and The Logic and Limits of the Federal Reserve Act (Menand 2022)

In these papers, Columbia University legal scholar, Lev Menand, recounts the political logic that led the US Congress to outsource the money creation privilege to private for-profit banks in the late 1800s and early 1900s. In a nutshell, there was a long-running and well-justified concern over the dangers of centralizing the money creation privilege within the federal government. In the end, Congress decided to decentralize the money creation privilege by outsourcing it to federally-chartered for-profit banks which would be supervised by a privately-owned quasi-governmental central bank (the Federal Reserve). The intention was for the money creation privilege to be distributed across local banks (roughly 40,000 at that time) with every locale having an opportunity to establish a bank (or more than one bank) without political interference or party control. The idea was that for-profit banks would ensure that newly created money went into productive investments that would spur economic development. Menand argues that it is time to re-evaluate the Federal Reserve system in light of the banking industry’s evolution since 1913, especially the proliferation of ‘shadow banks’. (One of the biggest evolutions has been conglomeration. Today, there are less than 6,000 banks and the four largest banks hold over 50% of the nation’s assets. This kind of concentration is the exact opposite of what the Federal Reserve Act was intended to promote.) NOTE: Decentralizing money creation by delegating it to private for-profit banks is only one of many ways that the money creation privilege can be effectively decentralized. Others include public banks, local governments, complementary currencies, and more.)

Contractions in Bank Money Creation Cause Financial & Economic Crises

Sudden contractions in money creation by banks explains a great portion of global financial instability

The Truth About Banks (Kumhof 2016)

Published by the International Monetary Fund and co-written by a former Barclays banker, this article highlights the claims of more detailed research papers which found that banks create money when making loans. The authors highlight their recent economic modeling which shows that much of the financial instability experienced around the world can be explained by sudden contractions in bank money. Unlike savings, bank money can evaporate virtually overnight in huge quantities.

Rapid contractions in bank money creation reliably predict banking crises and financial recessions – better than any other macroeconomic indicator

Credit Booms Gone Bust (Schularick 2012)

The authors and a team of international collaborators compiled a dataset of economic indicators covering 140 years and 14 countries (now 18). What was novel about the dataset is that it included bank money creation via lending (“credit creation”). The researchers found that financial crises are “more often than not the result of” rapid expansions and contractions in bank money creation. The presence of bank-created financial crises across the many countries and time periods studied suggests that the phenomena of bank-created financial crises is independent of national political leadership, economic system, and levels of economic development. A key insight of the paper is that “the financial sector is quite capable of creating its very own shocks” and that: “The frequency of crises in the 1945–71 period was virtually zero, when liquidity hoards were ample and leverage (debt to banks) was low; but since 1971, as these hoards evaporated and banks levered up, crises became more frequent.” The below chart showing this “oasis of calm” was published in a 2023 paper which drew on the same dataset.

Recessions caused by a contraction in bank money creation are three times deeper and longer, on average, than “normal” recessions

When Credit Bites Back (Jorda 2013)

Looking at 223 recessions across 14 countries and 140 years, researchers find that recessions are far more damaging and long-lasting when they are caused by expansions and contractions in bank-created money (“credit”). These ‘financial recessions’ typically last 5+ years and feature deep and permanent losses in economic productivity. This is significantly longer than normal ‘business cycle’ recessions that typically last only 1-2 years and feature a fast rebound in productivity that compensates for the slower period. In other words, banking crises cause financial market crises which lead to painful, destructive, and long-lasting economic recessions. In general, the greater the excessive bank money creation, the worse the recession that follows.

Bank Money Contractions Cause Explosions in Public Debt

Banking Crises: An Equal Opportunity Menace (Reinhart, 2013)

Looking across 200 years and 66 countries, Harvard Business School researchers show that, globally, banking crises are preceded by booms in bank money creation (‘credit’) that produce asset price bubbles, usually in real estate and stock markets. These bank-fueled financial crises produce long-lasting economic damage to countries. On average, they leave governments with an 86% increase in debt due to the evaporation of household incomes (and therefore tax receipts) alongside rising need for government assistance. Importantly, their research shows that countries have figured out how to completely stop banking crises from happening, but that these lessons have been forgotten. During a thirty year period following WWII, there were virtually zero banking crises across the 66 countries studied. As the study notes, national governments around the world imposed tight controls on bank money creation during that era of stability, which ended when many nations de-regulated their banking industries in the 1970s and 1980s.

Bank Money Creation Can Be Used to End Financial Recessions Overnight

Credit and Economic Recovery: Demystifying Phoenix Miracles (Biggs, 2010)

This paper shows that systemic financial crises – and the damaging financial recessions they commonly induce – have been brought to a “sudden stop” at least 22 times in the last few decades by simply restoring the flow of bank credit into the economy. The paper argues that mainstream economists have misunderstood the role of credit flows because they focus almost exclusively on the stock of credit rather than on the inflows and outflows of credit. Consistent with other researchers, the paper finds that drops in the inflow of credit signals both the onset of financial recessions and that financial recessions end in step with the rate at which credit inflows are restored.

Financial Recessions Are Particularly Damaging to Democracies, Frequently Giving Rise to Right-Wing and Authoritarian Governance

Going to Extremes: Politics after Financial Crises, 1870-2014 (Funke 2015)

Researchers married Moritz Schularick’s dataset on bank money creation and “financial recessions” up to big multi-century and multi-country political science datasets in order to analyze the impact of financial recessions on social and political conflict. They found that after a recession that originates in the financial sector voters swing to the political extreme right, often attributing blame for the crisis to minorities or foreigners. Social unrest and a rise in authoritarian governance frequently follow, with extreme right parties gaining 30% of the electorate within 3 years of the onset of the crisis, on average. “Importantly, we do not observe similar political dynamics in normal recessions or after severe macroeconomic shocks that are not financial in nature.”

The Field of Economics Has Mistakenly Left Bank Money Creation Out of its Models and Teaching

Banks are not intermediaries of loanable funds — and why this matters (Jakab 2015)

Published by the Bank of England, this seminal paper shows that prior to the 2008 recession most mainstream economic models of the economy did not include banks, at all. This omission has been widely recognized as a big factor in mainstream economists’ failure to predict the crash. After 2008, many economists began incorporating the banking sector into their models of the economy. However, as this paper shows, this new generation of economic models are built on the mistaken belief that banks lend out depositors’ savings, which they do not actually do. Therefore, the paper’s authors develop and publish the first mainstream economic model that correctly incorporates the truth that banks create new money every time they make a loan. The authors compare the predictions of their new model against the mistaken mainstream models to show that the models produce dramatically different results. Unlike the models that assume banks lend out depositors’ savings, their new model accurately predicts how and why bank money creation and destruction causes the dramatic swings in the quantity of money that led to the 2008 crisis and many other financial and economic crises. (See the authors’ 2019 paper for more detailed analysis and history of macroeconomic models and their shortcomings regarding bank money creation.)

Financial Crises: Economic Models vs Accounting Models (Bezemer 2010)

This paper describes how mainstream economists failed to predict the 2008 financial crisis because they primarily rely on hypothetical mathematical models of the economy, rather than modeling the economy through an actual accounting of money flows in the economy. The author shows that mainstream economists’ mathematical models did not include bank money creation in their mathematical equations and therefore could not anticipate or explain the 2008 crash, which was caused by a large expansion and contraction in the rate of bank money creation. The paper analyzes the history of economic thought and practice to answer how such a large blind spot developed in mainstream economics. It also presents a largely-forgotten method of economic modeling based on accounting which was effective both in predicting and explaining the 2008 crisis. One of the defining characteristics of these accounting-based models is that they include bank money creation (as credit/debt). (Note: In the aftermath of 2008, many mainstream mathematical models were updated to include the banking sector, but most fail to model bank money creation correctly, as called-out in the 2015 and 2019 Bank of England papers by Jakab and Kumhof, above.)

Open Letter: Rethinking the Role of Banks in Economics Education (Rethinking Economics 2019)

In 2019, economists and economics students at dozens of universities wrote an open letter to the economics profession, saying: “Economics textbooks across the world continue to teach students a model of the monetary system in which commercial banks act as intermediaries, that only move existing money around the system, like lubricant in a machine… Many economics courses rely on the models in these textbooks, without recognising the empirical evidence that undermines them…. This gives an unbalanced view of the way the monetary system functions and of the role of banks in the economy… These models, taught without balance or regard for existing evidence on the financial sector, lead economics graduates to draw flawed conclusions. Today’s economics students will become the policy-makers, economic influencers, politicians, financiers and business leaders of the future. To create stable and productive economies globally, they must have a real-world understanding of banks and money creation.”

Commercial Banks Have Substantial Control Over the Governance of the Federal Reserve

Unrepresentative and Unaccountable (The Center for Popular Democracy, 2021)

This paper illuminates the voting structure of the Federal Reserve regional governing boards, which enables financial interests to elect 2/3s of the board members.

Making the Federal Reserve Fully Public: Why and How (Haedtler, 2016)

In the United States, the Federal Reserve System is comprised of 12 branch banks overseen by a governing board. The 12 branch banks are privately-owned for-profit corporations that are not subject to freedom of information requests and many other federal regulations. The dividend-earning shareholders of the 12 branch banks are the private commercial banks in each region. (Around the world, many central banks began as privately-owned for-profit corporations, but the Fed is one of the last ones that has not been made publicly-owned.) The bank “member” shareholders select 2/3s of the governing boards of each branch and influence the selection of its President, giving them substantial say over monetary policy. There are obvious conflicts of interest between this arrangement and the Federal Reserves’ role as the regulator of commercial banks. (If one doubts the influence of private banks within the Fed, read the 2010 congressional investigation of the bail-out of AIG in which members of Congress are furious about NY Fed President Timothy Geithner’s wholesale adoption of JP Morgan Chase's bail-out plan, which enriched JP Morgan Chase to the detriment of tax payers and AIG shareholders.)

The Federal Reserve’s Monetary Policy Statistically Favors Unemployment and Republicans

The Fed's Real Reaction Function Monetary Policy, Inflation, Unemployment, Inequality (Galbraith, 2007)

This paper uses statistical analysis to evaluate empirically whether the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy is more responsive to inflation or unemployment (the two parts of its “dual mandate”). Surprisingly, the statistical analysis found that the Fed’s policy is uncorrelated with inflation but is negatively correlated with unemployment (meaning that when unemployment gets very low the Fed tightens monetary policy, which typically induces a recession and an increase in unemployment). The paper also found that in the year before a presidential election, there is a significantly tighter monetary policy coming from the Fed if a Democrat is in office and a significantly looser policy if a Republican is in office. These effects are statistically significant, allowing for controls.

The Field of Economics Is Remarkably Uncritical of the Federal Reserve, Perhaps Because It Is Captive to It

Priceless: How The Federal Reserve Bought The Economics Profession (Grim, 2013)

The Federal Reserve, through its extensive network of consultants, visiting scholars, alumni and staff economists, so thoroughly dominates the field of economics that real criticism of the central bank has become a career liability for members of the profession, an investigation by the Huffington Post has found. This dominance helps explain how, even after the Fed failed to foresee the greatest economic collapse since the Great Depression, the central bank has largely escaped criticism from academic economists. In the Fed's thrall, the economists missed it, too.

Banks and Shadow Banks Own or Have a Controlling Interest in the Vast Majority of Multinational Corporations

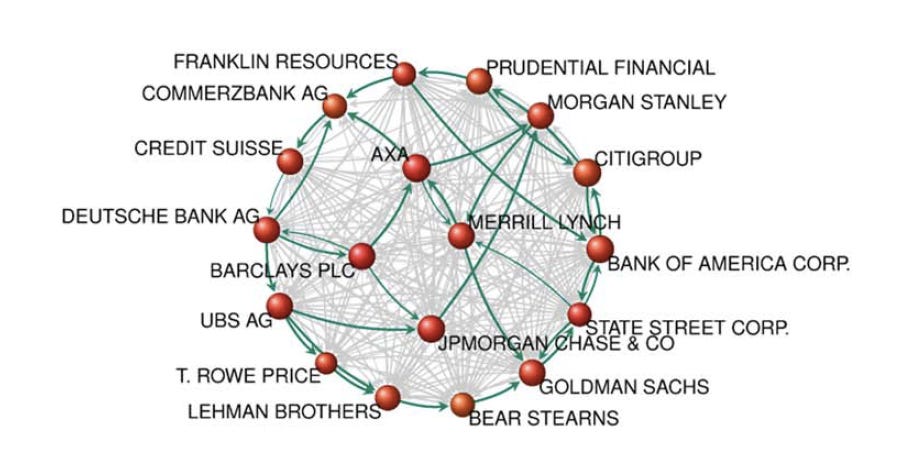

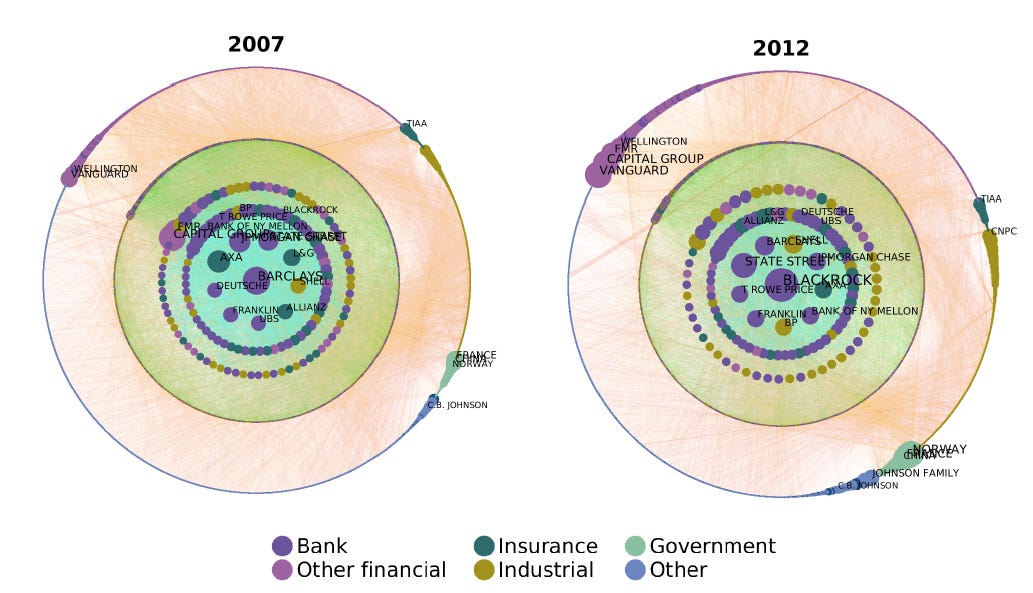

The Network of Global Corporate Control (2011)

Researchers mapped the ownership and directorship links between tens of millions of multinational corporations (both publicly and privately held firms). They find that only 737 firms have accumulated 80% of the control over the value of all multinational corporations. Even more concentrated, “a small tightly-knit core of (mostly) financial institutions” form a “super-entity” that controls nearly 40% of the value of all multinational corporations. This means that network control is much more unequally distributed than wealth and that it is most concentrated within financial firms (primarily banks and shadow banks, such as investment banks, private equity, hedge funds, and money mutual funds).1

The Architecture of Power (Glattfelder 2019)

Glattfelder and his team expanded their “Network of Global Corporate Control” analysis to see how the control network changed over time, specifically before and after the 2008 financial crisis. What they found was that it became more concentrated. The number of (mostly) financial corporations in the most dominant group consolidated by 26%. They show that the extreme concentration of control in this core group of firms represents a potential misalignment with societal and ecological wellbeing. The tightly interconnected firms “may have aligned interests that are not fully aligned with the economy and society as a whole”. For example, their investments and profit interests likely make them powerful antagonists to climate action, shutting down corporate tax evasion, breaking-up monopolies, and more strongly regulating the financial sector.