Why has the money supply declined so rapidly? Here's what I learned after much research...

Plus, two new tools reveal the many transactions that create and delete money from the economy's money supply: The Monetary Crosswalk & Monetary T-Account Index

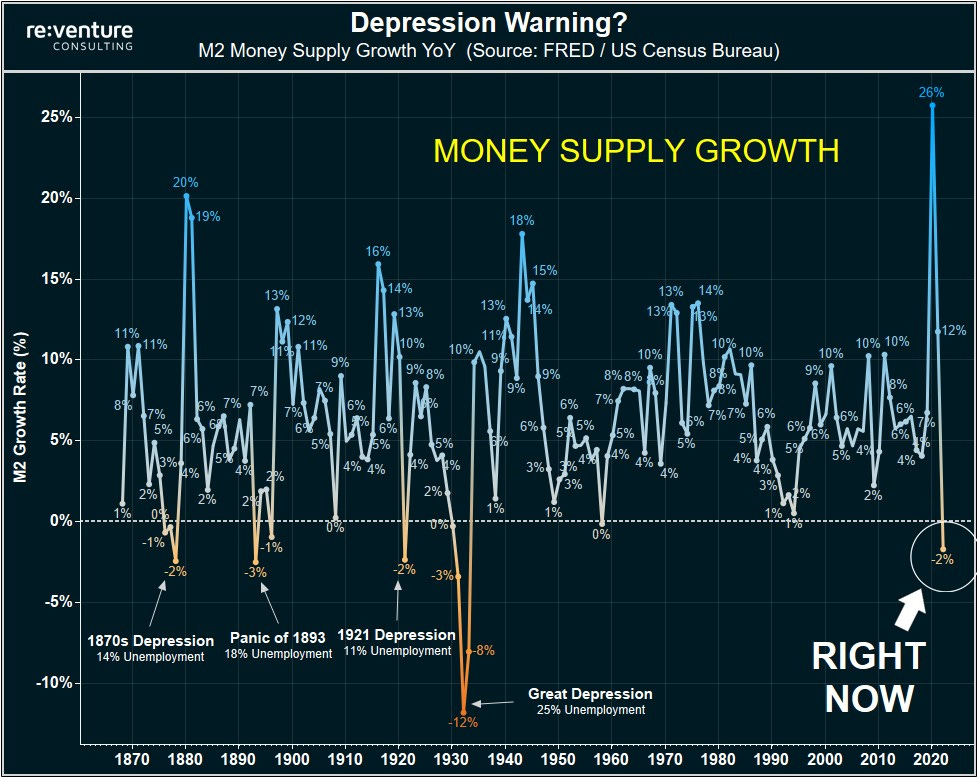

Since 2022, the amount of money in our economy has declined by 4.5%.1 That is a bigger drop than the first year of the Great Depression, which is the last time the nation’s supply of money declined by a similar magnitude. (Read this before continuing if you aren’t familiar with the idea that money can permanently disappear from our economy in huge quantities.)

Why does a decline in the amount of money matter?

While 4.5% may not sound like much, history shows that our economy’s health typically suffers when there is a decline in the quantity of money. That makes sense. If there is substantially less money available for people to transact business, less business gets transacted, which causes organizations to cut the goods and services they offer and lay off employees.

For example, the Great Depression began with a decline in the money supply of 3% in 1930, then 12% in 1932, and finally 8% in 1933. Cumulatively, the money supply decreased by a whopping 30% in three years. Imagine how the economy would be functioning three years from now if there was 30% less money to go around! Scary thought, right? That’s what happened in the Great Depression. The result was 25% unemployment.

Obviously, it was not inevitable that the 3% drop in the money supply in 1930 would cascade into a 30% decline over the following two years. There were and are many things that can be done to avoid such a slide. After all, the quantity of money in existence is entirely within the control of humans!

How concerning is today’s decline?

Whether one should be concerned about a 4.5% decline in the quantity of money depends on why the money is disappearing. If the decline is being caused by something that will naturally reverse itself, then the worry does not need to be great. On the other hand, concern should be high if the cause of the decline is something that will be difficult to counteract, or something that is going to naturally pick up speed like a snowball rolling downhill, such as a debt-deflation spiral.

So, what has been causing the rapid loss of money?

I thought it would be simple to find out why the money supply has dropped so much and so quickly since mid-2022. But the more articles I read, the more concerned I became. Some of the articles offering answers contradicted each other. Others equivocated, saying, “it could be this or it could be that” while making no attempt to nail down the causal importance of either. Some said, “it is this, plus that, plus this other thing” without trying to make the math add up to the decline we were witnessing.

That’s why I was somewhat comforted when I read a blog post by Joseph Wang, a former Federal Reserve economist and author of Central Banking 101. Basically, he says that the multiplicity of ways money is created and destroyed introduces so much complexity that it is “very difficult” to identify the cause of a decline in the quantity of money.

Why would it be comforting to know that it is virtually impossible to deduce the true cause of a decline in the amount of money in the economy? Because I’d come to that same conclusion during many hours of research, but I thought I must be misunderstanding something. Once I saw Wang confirm what I had concluded through my own research, I finally began to trust my own work a little more.

What does it all mean?

When I stepped back and looked at the research I’d compiled, I realized that the work I’d been doing was pretty cool, and possibly of service to others. I recently gave a talk about this research at the 2023 International Monetary Conference hosted by the American Monetary Institute. (see the video and tools linked below)

My research led me to some rather surprising conclusions:

It is entirely possible that our current monetary system is functionally ungovernable.

It may be inadvisable to rely on any existing models of our current monetary system because massive gaps in data availability mean it is impossible to validate any models at this time, including accounting-based models.

“Sovereign money” reforms may not resolve the complexity or governability challenges of our current monetary system.

I know those are big claims. I’m happy to be corrected.

Research Contributions

The work-in-progress tools created as part of this research can be found here:

In the talk, I give appreciations to several researchers that have inspired and collaborated on this research. A special shout-out goes to Benjamin Whitehurst, an MBA student at North Carolina State University, who has also put in many hours compiling the Monetary T-Account Index and checking over the Monetary Crosswalk.

Collaborators Welcome

If you are a researcher who would be interested in further developing or publishing about the Monetary Crosswalk and/or Monetary T-Account Index, please reach out at the email address below. I have several ideas for how to take the project to the level of being worthy of publishing but they are beyond my capacity to do single-handed.

If you have thoughts about of this, you can email me a sam.hummel@duke.edu.

I am well aware that M2 (cash + bank account balances) is only one measure of the quantity of “money” in the economy. Some people will say that if other “money-like” financial products are included in the measure of the money supply, the amount of money may not be declining after all. Examples of “money-like” or “near money” financial products include shares in money market funds, Treasury bills (T-bills), marketable securities, and repurchase agreements (“repos”). While these can be passed around within the financial sector almost as easily as money in a bank account, they are virtually useless for buying real goods and services in the real economy. That is because they are really financial products which must be converted into bank account money or cash before they can be used to purchase anything in the real economy. When there is a banking, financial, or economic crisis, history shows that it often becomes very difficult, if not impossible, to convert these money-like financial products into bank account money (without incurring huge losses in the process). I do not consider a financial product that has to be converted into usable money to be money, itself – especially when that conversion typically becomes impossible during crises when having usable money is of paramount importance.